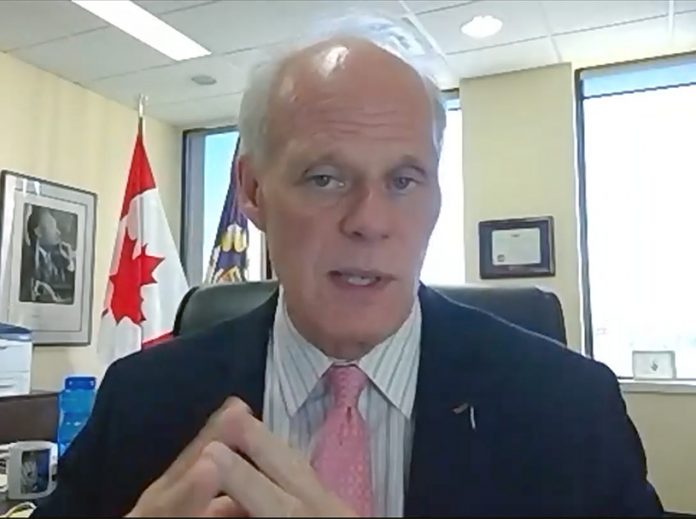

The opioid crisis is a national health epidemic Oshawa faces, said Mayor Dan Carter.

Since being elected in 2018, Carter has worked with existing organizations and other city officials to implement a variety of outreach programs designed to connect people who are homeless and affected by substance abuse issues with the necessary supports.

The city, along with the help of community organizations, has housed more than 300 homeless people in the last year-and-a-half. Carter said there are still about 167 people across Durham region who are “unsheltered, living rough, and seeking assistance.”

In an address to Durham College student earlier this month, the mayor, who has been sober for 30 years, was open about his history of addiction and time living on the streets in his late 20s. Carter spent time in Los Angeles at a drug and alcohol rehabilitation centre.

When he returned to Canada in the early 1990s, Carter turned his passion for people and community into a journalism career and got involved with local politics.

“I wasn’t being punished, I was being prepared,” Carter said about his addictions. “I was being called to service at a time that all of these events in my life were happening in our community.”

Oshawa first responders receive approximately 600 opioid overdose calls and see 70 deaths annually, Carter said. The crisis has been “festering or smouldering” in Canada for the last 20 years, he added.

Carter has talked to the prime minister, premier and minister of health about the importance of recognizing the opioid crisis across Canada as a national health epidemic. Carter said recognizing the issue on a national scale is the first step in creating a Canada-wide strategy to combat the rising death toll.

The Oshawa Micro-Housing Pilot Project is an example of a solution the city and region have in place to address the issue of homelessness, Carter said. The project will see 10 units going up in central Oshawa, at the corner of Olive Avenue and Drew Street.

Erin Valant, housing services program manager for Durham region, said the units are on track for people to move in before the holidays.

The project is designed to be transitional housing, she said.

As people “identify that they want more independent living,” Valant said, “we’ll help them move out into the community.”

The project uses what Valant calls the “housing first model” to provide the people who move into these units with a case manager dedicated to helping that person remain housed while achieving their goals.

Durham region and Oshawa have partnered with Lakeridge Health to provide “dedicated mental health and addiction support staff for the folks that are going to be living there,” said Valant.

“There is a lot of stigma around homelessness,” she said. But that experience is not unique to Durham region and the staff behind the project work with the community to make sure they know about the micro-housing opportunity.

“I don’t have all the solutions, but I am committed in regard to taking on these issues and trying to find a solution as we move forward,” said Carter.

For those living on the streets and looking for assistance there are also programs supported by the city including the Paramedic Outreach Program, the Welcoming Streets program through Carea Community Health Centre and the Back Door Mission, said Carter.