Editor’s Note: This story is part of a series called the Land Where We Stand (LWWS). Uncovering the hidden stories about the land our community is built on is what the Chronicle’s feature series, the #landwherewestand

“Oshawa was built on its industries. We had numerous large scale industries, all of these huge, large-scale industries, and none of that is left,” says Jennifer Weymark, the archivist at the Oshawa Museum.

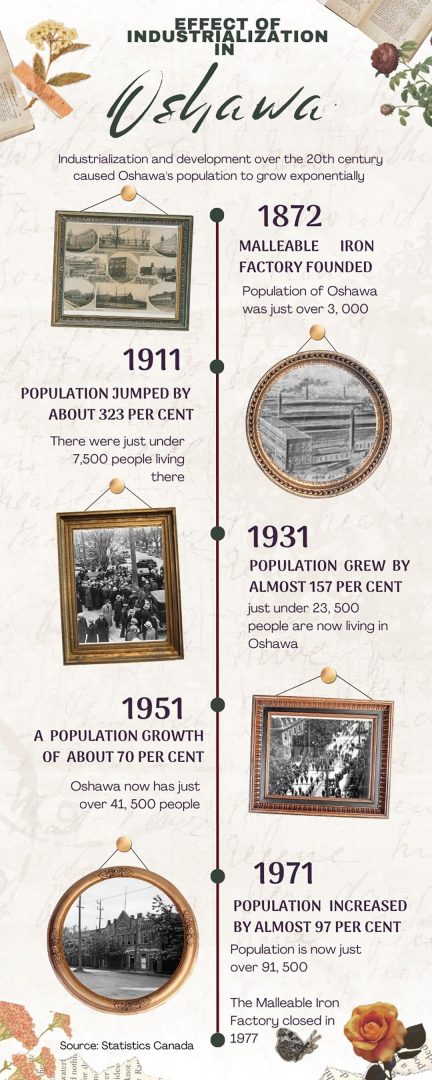

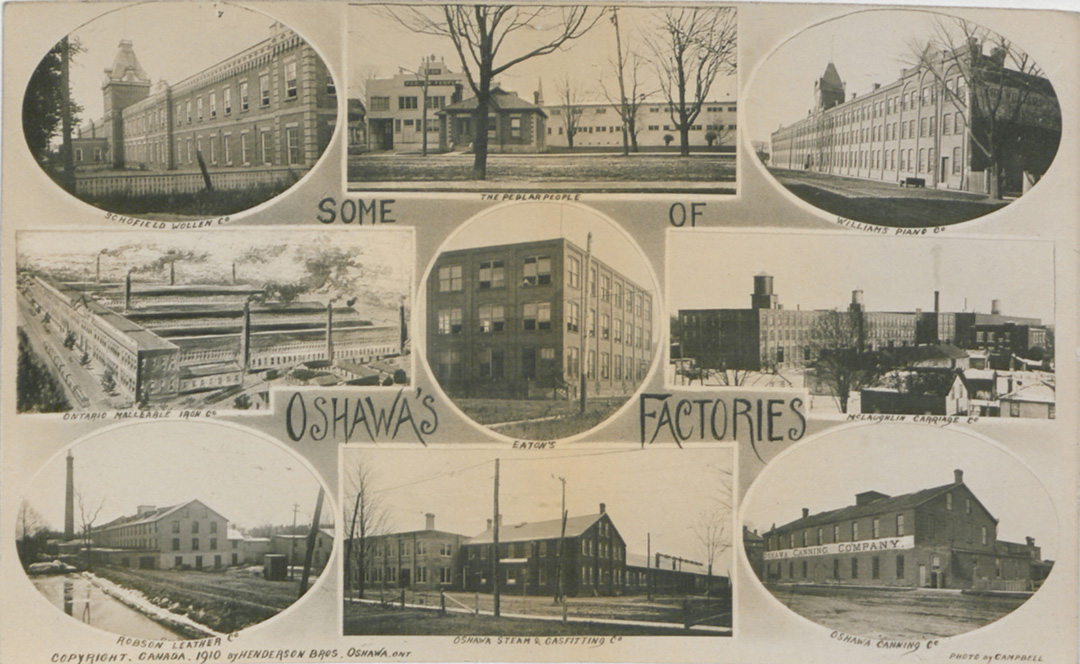

The industrial revolution arrived in Oshawa in the early 1900s, transforming the small town to a thriving industrial city, and giving it the nickname: “Manchester of Canada.”

The rise of industry contributed to the growth of Oshawa and Durham Region with General Motors establishing its Canadian headquarters in the city in 1918. But before GM arrived, there was another factory that played a critical role in Oshawa’s industrialization – the Ontario Malleable Iron Company (OMIC).

“There’s no buildings remaining other than this building,” Weymark says.

Founded in 1876, OMIC became one of the largest employers in Oshawa, providing jobs and a sense of community for generations of workers.

As the name would suggest, the factory produced iron products such as small to large pipe fittings, automobile and railway car castings and agricultural equipment.

At its peak, OMIC employed anywhere between 350 to 800 people a year and was an integral part of the city’s economy until it ceased its operations in 1977 after a labour dispute.

Metrolinx now owns the property and plans to repurpose the OMIC factory as a new GO Transit train station. However, this decision was met with opposition from many members of the community who not only want to see the building preserved in its original form but want to see the industrial history of Oshawa preserved.

Jane Clark, an Oshawa resident and former Heritage Oshawa member, is one of the people fighting for the building’s preservation. She argues that the preservation of local history is crucial and says individual and community stories are what give people and towns their identities.

“These properties, particularly Malleable Iron, are a huge part of Oshawa’s past and therefore its identity,” she says.

“They wouldn’t have a city if it weren’t for Malleable Iron and those other factories,” says Jane Clark.

Plans for the GO train station include protecting the façade of the building, as it was designated a heritage site with value or interest under the Ontario Heritage Act.

Clark prefers giving the building a functioning purpose, such as making it a “culturally significant hub” since it’ll be a place where people travel through.

“It’s supposed to be the compromise, but just gutting a building is not the best option. If it had a collection of shops, cafes, art spaces, green spaces and things like that… people would appreciate that and learn what it used to be,” she says. “Its new role could be as a gateway into Oshawa and a marker of our pride and our past.”

As Oshawa has continued to grow and evolve, many of the city’s historic industrial buildings have been demolished or repurposed for new uses. However, there has been a growing movement to preserve these buildings and their associated history.

Weymark emphasizes the impact OMIC had on the growth of Oshawa’s population.

“It brought people to the area. I mean you came here to work,” she says. “Post World War One and Post World War Two, we had large scale immigration into the area and this was one of the major employers of new Canadians arriving.”

Oshawa’s industries provided the new immigrants with opportunities. Along with OMIC, Oshawa had General Motors, Houdaille Industries Inc., TG Gale Lumber Co., among others.

Despite the shift away from industrial jobs in recent years, that industry made Oshawa what it is today. According to Julie MacIsaac, the director of innovation and transformation at the City of Oshawa, the manufacturing sector made up around 91 per cent of all jobs in the city in 1991.

However, like many early twentieth century factories, OMIC left both positive and negative effects on the city. The factory’s operations had a significant impact on the environment, particularly on the nearby Oshawa Creek, which was polluted with metals and other contaminants.

Amanda Robinson, an academic associate in the liberal studies program at Ontario Tech University, has written about the role of industrialization in reshaping Oshawa’s creek.

In her research, she discovered a 1902 municipal proposal stating that 50 years of industrial activities made the water in Oshawa Creek unsafe for human consumption.

Robinson, who teaches in the Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, mentions water as an important ingredient in the building of industry in Oshawa and highlights the importance of it to a community’s culture.

“What’s so interesting and paradoxical about water, in addition to providing life, it provides a form of power for early industrial activities during Canada’s first wave of industrialization,” she says. “But it is also a place where working class people go to swim, to picnic, to skate in the winter.”

The rapid industrialization in the area also had an impact on the Indigenous population who used the land and the creek as part of their subsistence economies. These practices were displaced by industrialization.

Robinson says from a settler colonial perspective, the effort to gain land in service of the industrial project was a form of Canadian nationalism, and Oshawa’s industrialization was a segment of that nationalism.

“A lot of that industrial activity is framed around, from a public relations standpoint, this sort of like claiming ownership over the land and celebrating industrialization as looking forward,” she says. “Indigenous peoples aren’t really considered.”

Robinson also says its important to preserve the histories of these factories because many people in and around these area may never have had an opportunity to record their stories.

“It’s important to see the humanity of the people who were working in these industries… we don’t have a lot of those stories left in some cases,” she says. “If it’s not preserved, then we are sort of saying that those stories of working class people and their experience with industrial landscapes aren’t worthy of commemoration.”

The fight to save the OMIC building has been ongoing for more than a decade, with a group of local activists, including Heritage Oshawa leading the charge.

Despite the efforts of the community, the fate of the OMIC building is still uncertain. While there has been some progress in preserving the building, the final decision rests with the city and Metrolinx, who have not made any further comments on the fate of OMIC.

However, the fight to save OMIC has brought attention to the importance of preserving local history and heritage on the land where we stand.

Weymark says it’s important to preserve the history that we still have left. “[OMIC] is the last vestiges of Oshawa’s industrial past,” she says.