co-written with Hafed Almadani

Editor’s Note: This story is part of a series called the Land Where We Stand (LWWS). Uncovering the hidden stories about the land our community is built on is what the Chronicle’s feature series, the #landwherewestand, is about.

Long before settlers arrived in Canada, this land was home to a rich and diverse range of Indigenous peoples, all in varying stages of organization.

These communities had their own belief systems, cultural practices and ways of living. Though sometimes these beliefs, often distinct from each other, occasionally overlapped.

The Indigenous peoples lived off the cherished land and moved all around it since time immemorial.

However, everything changed with the arrival of the British and French colonizers.

The land where we stand today, Oshawa, derives its name from the Ojibwe term “aazhaway,” which means “the crossing place” or “a place where a canoe was exchanged for a larger vessel.” This likely refers to the location of Oshawa at the mouth of Oshawa Creek, where it empties into Lake Ontario.

Historically, this location was an important meeting place for Indigenous peoples to exchange materials between different tribes and communities, creating a stable form of trade.

When Europeans arrived in the area in the 18th century, they anglicized the name to “Oshawa,” which has been used ever since. The city of Oshawa was officially incorporated in 1850 and has since grown into a thriving community, with a population of over 160,000 people.

Before European settlement, Oshawa and the surrounding region were already a diverse Indigenous territory, home to several different Indigenous communities. Among these communities were the Mississauga Ojibwe, the Huron-Wendat, and the Haudenosaunee (also known as the Iroquois).

Melissa Cole, the curator at the Oshawa Museum, spoke about the work that went into the exhibition showcasing Indigenous history in Oshawa.

“So based on the exhibit that we created in 2017 one of the first groups that we, first Indigenous communities, that we talk about is the ancestral Wendat,” she said. “There’s evidence from about 1380 to about 1450 and around the 1600s”

Archeological digs at the Grandview and MacLeod sites provide evidence of their presence in Oshawa dating back to the Terminal Woodlands Period 1000 to 1615. This period of time began when the people living in Southern Ontario became full-time agriculturalists.

According to Cole, the excavation of these sites provides compelling evidence of Oshawa’s historical truth.

“For me, what these sites tell us is that Oshawa’s history does not begin with the white man that settled here from Vermont and typically that is how our history is told in our community is, you know, the first settler was Benjamin Wilson. We have signs in the park that irritate me, and he was not the first settler,” said Cole.

The Grandview site, located at the corner of Taunton and Grandview Street North, was discovered in 1992 during preparations for a new subdivision. Buried beneath many layers of soil, 12 longhouses were found, along with many other artifacts.

This site is said to have been inhabited during the Terminal Woodland Period, from 1400 to 1450.

In 1967, the MacLeod site was first discovered at the corner of Thornton and Rossland. The village located here was roughly three to four acres and had five longhouses.

The real interesting part of these two sites is their connection to each other. The MacLeod site was inhabited from 1450 to 1470, which has led researchers to believe those living at the Grandview site relocated to the MacLeod Site

‘”He [Benjamin Wilson] was the first European to come to this land but there are others that were here first,” said Cole.

During this period, the Ontario Iroquois were the recognized inhabitants of the Durham Region, their presence dating back to the tenth century. At this point, tribal or First Nation designations were not used.

With the increased change from ‘food collecting’ to ‘food-producing,’ there was an enormous change in the social and cultural aspects of Indigenous people’s daily lives. The intensified involvement in clearing fields, preventing weed growth and protecting crops from animals and birds created a more sedentary lifestyle, allowing for a stable food supply to be stored for the winter months. This eliminated the need for groups to split up during certain parts of the year in search of food.

With this advancement in agricultural practices, trade relations began to grow in importance to the early economics of the time. Crops, pottery and woven items were traded to the Algonkian tribes in the north, which were then traded with neighbouring villages for tobacco and stone tools.

With the arrival of the Europeans, this trade system, which had lasted for years, switched to favour the European items in exchange for beaver furs.

As Pam Schreiber writes in Not Forgotten: Urban Aboriginal People in Durham Region: “It was also during this time period that the Roman Catholic Recollect and the Jesuit missionaries arrived.”

“The arrival of the Europeans led to the destruction of the Ontario Iroquoian and Algonkian Nations,” she said.

“Diseases, such as measles and smallpox, devastated the unprotected population in large unprecedented epidemics, such that an estimated 90 per cent of the population vanished.”

The European arrival also created social conflicts between nations that had been Christianized and those that remained connected to their traditional roots.

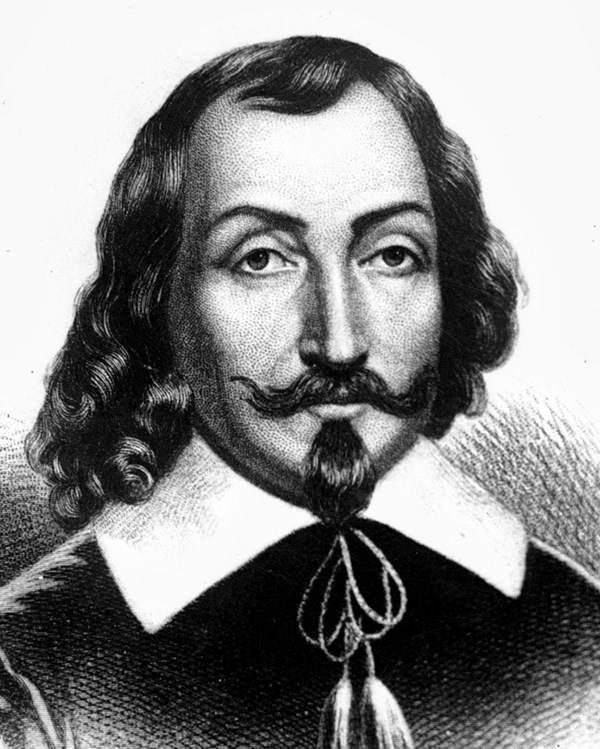

Since Indigenous people of the day relied on oral recounts of times, the first written accounts of Ontario were discovered in the journals of Samuel de Champlain, who visited the Huron in 1615 to form trade agreements.

This was long before settlers arrived in Canada.

The land where we stand today may be vastly different than the land of the original communities that inhabited it and the proof of this may be buried – but colonization didn’t take Indigenous people off the land.

Their beliefs, customs and ways of life prevailed through the horrors brought upon them and continue to shine today.