Canadians are protected from criminal harassment by laws that keep people safe.

In fact, if you walk into any hospital in Ontario, you will see signs posted stating threats, harassment and violent behaviour will not be tolerated. People expect to feel safe when doing their job. When they don’t, actions are taken to remove the threatening party.

What if this wasn’t the case?

Female journalists are facing an increase in online harassment, targeted hate, threats of violence, rape and even death. The worst part is these aren’t always just threats. According to the Canadian Association of Journalists in August 2022, there appears to be a “coordinated online campaign” of hate directed at journalists who are female and even more for those who are persons of colour.

Too often these threats are not being taken seriously, so the hate continues.

According to a 2021 survey done by the Canadian-based non-profit Journalists for Human Rights, women journalists are targeted at a rate 3 times higher than their male counterparts.

Lisa LaFlamme, former chief anchor, and senior editor of CTV National News says the greatest attacks now come from social media.

“Anonymous, vitriolic attacks that confirm being a female journalist still makes you a mark for trolls no matter how much ‘real world’ progress is made,” says LaFlamme in a 2020 Journalists for Human Rights article.

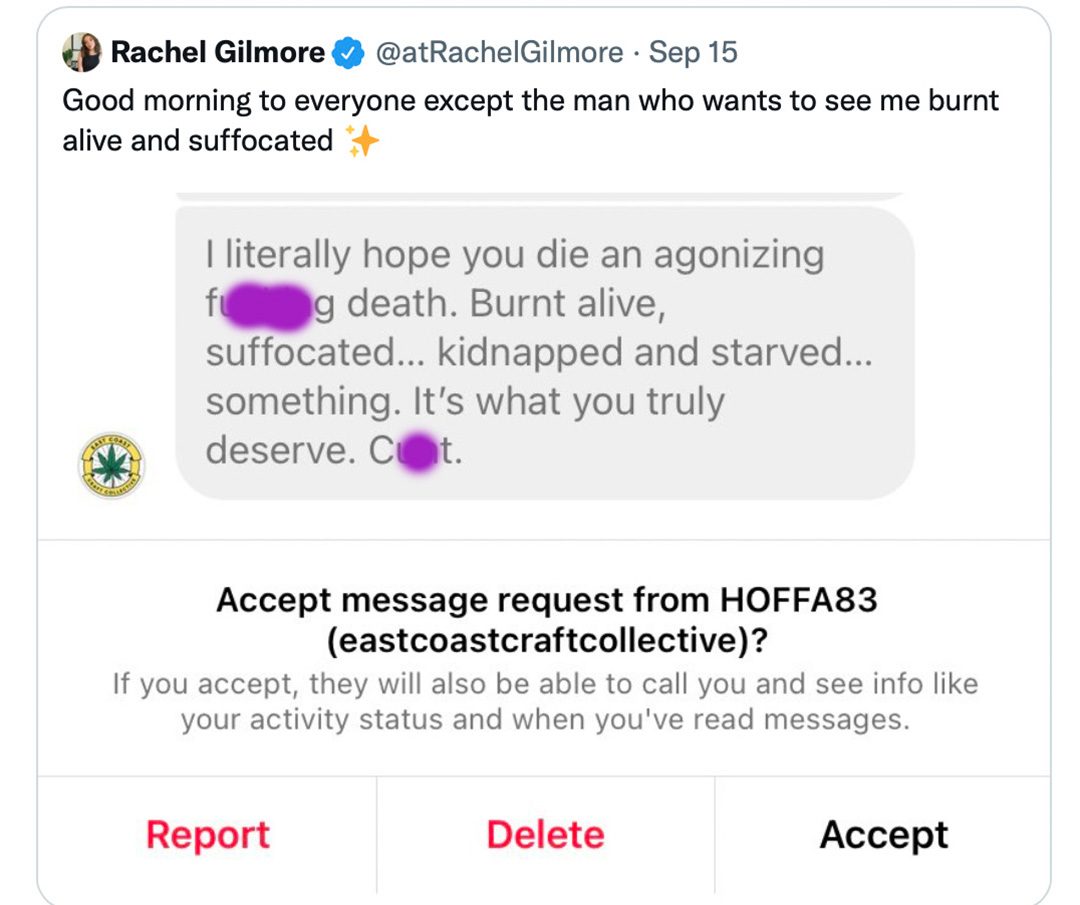

On September 15, Rachel Gilmore, a Global News reporter shared a message from her inbox on Twitter. The message says “I literally hope you die an agonizing f*****g death. Burnt alive, suffocated… kidnapped and starved… something. It’s what you truly deserve. C**t.”

If this was said to a doctor while they were doing their job, surely something would be done about it. No doctor deserves to be spoken to that way. So why is it so widely accepted when journalists are the ones receiving the hate?

Brent Jolly, President of the Canadian Association of Journalists, says he thinks this is a larger problem than originally thought.

“It’s really sad and troubling as to the degree to which this has been almost normalized,” says Jolly in a 2022 Reuters article.

It doesn’t help when politicians tell their followers to “play dirty” with journalists and tweet out their email addresses. Maxime Bernier was forced to take down such a tweet but not before CTV journalist Christy Somos received messages saying she should be sexually assaulted, murdered and told to kill herself.

A 2019 survey done by the Committee to Protect Journalists showed that of the female and non-gender conforming journalists asked, more than 70 per cent said they had experienced safety issues in the U.S. and Canada with verbal harassment and online harassment being the most common types.

Whose job is it to ensure journalists are safe?

These women can report online and verbal attacks and hope it stops at that but real action doesn’t seem to be taken until someone is physically attacked, raped, murdered or just scared for their lives.

It is time something more is done.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau says police must take threats to journalists seriously. The only way to regulate this is through policy. Unfortunately, too often policies come into place after enough people are seriously hurt.

Let’s hope this changes before another journalists faces violent threats, or worse.