Editor’s Note: This story is part of a series called the Land Where We Stand (LWWS). Uncovering the hidden stories about the land our community is built on is what the Chronicle’s feature series, the #landwherewestand, is about.

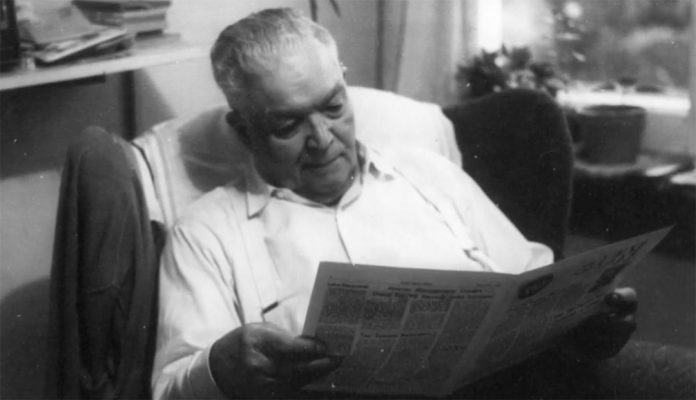

Not many people can look around in their 80s and see the family home they spent most of their life in, but Ward Pankhurst can.

“My sister was born right up here where I – where I sleep now. I’ll be 84 this year,” Pankhurst said in a 1972 interview with Oshawa Museum staff.

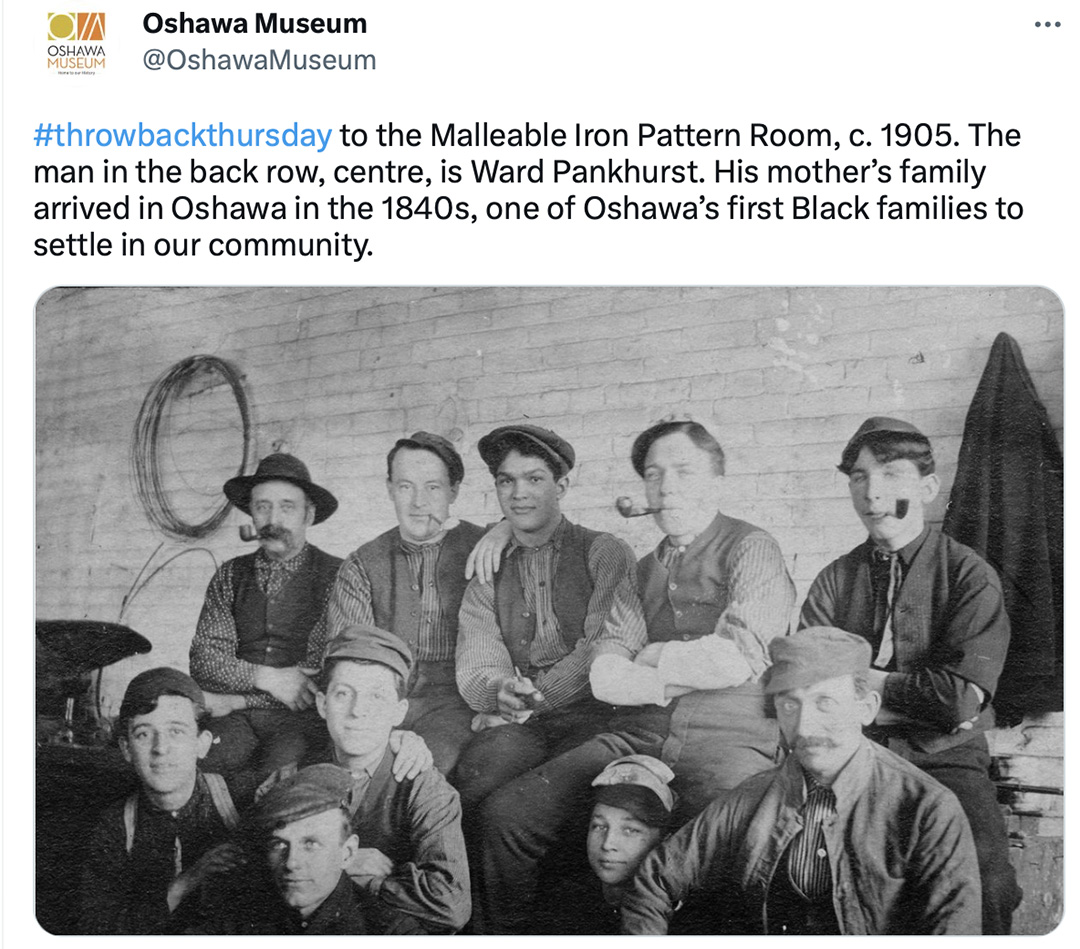

Born Ward Delayfayette Pankhurst in 1888 to parents Henry and Margaret (Dunbar) Pankhurst, his mother’s family were some of the first Black settlers in this area when they arrived in the 1840’s, even though many people to this day think Black settlers came much later.

“My mother was born here but her people came up from Lower Canada in 1840, I think it was,” Pankhurst said. “You know it was just Lower Canada and Upper Canada.”

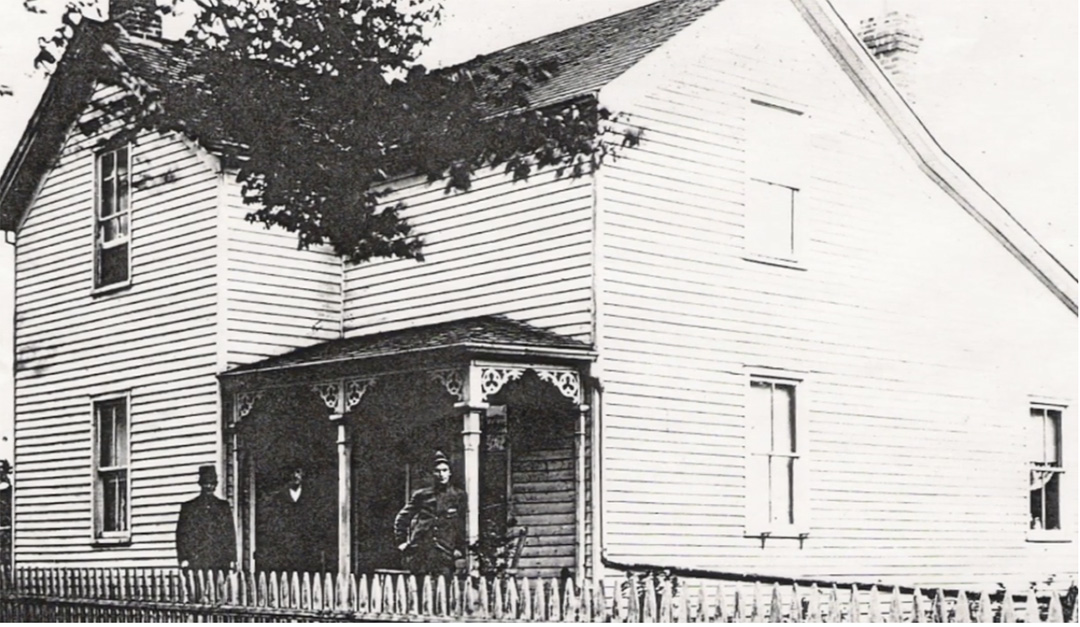

Pankhurst and his mother were both born in Cedar Dale – now South Oshawa, their family home on Cedar Street. They lived there from the 1850s to the 1980s. The Pankhurst family home still stands today on Cedar Street in South Oshawa.

He was the second of three children. His older brother, Albert, was born in 1885 and his younger sister Greta, in 1895.

World War I affected the Pankhurst family, as it did so many others.

Black men were not always welcomed into the armed forces. Those who did try to enlist were met with protest and backlash even after the federal government stated they could not be denied based on race, according to Oshawa Museum Archivist, Jennifer Weymark.

When most Black men in the Canadian forces served in WW1, it was with the No. 2 Construction Battalion, a segregated battalion that faced hostility and racism, Weymark said.

Both brothers would come to have a very different experience with this.

Albert enlisted in 1915. He was able to identify with his father’s ethnicity and served in both the 28th battalion in Portage La Prairie in Manitoba and previously with the 34th Ontario Regiment, which would not have been desegregated, according to Weymark.

He was declared missing in June 1916, and became a prisoner of war (POW) on July 19, held at Dulmen, Germany. He was held in three different camps until he escaped in March 1918, according to his personnel file.

Pankhurst was in the United States while his brother was a POW. He was part of the first wave of men registered for conscription, though there is no evidence that he actually served, Weymark said.

“If he did, it would have been a very dramatically different experience than his brother who was serving in the non-segregated unit,” she said.

Pankhurst listed Caucasian under race on his draft card but Weymark said that was scratched out and Black was written above it.

“If Ward had served, because they made that change on his draft card, he would have been put in the segregated unit,” she said.

Pankhurst eventually came back and lived his life with his sister in their family home. In his interview with the Oshawa Museum, he talked of life in what would become Oshawa.

“We had a ball team and they started in ’13 – we started the town league,” Pankhurst said in his 1972 interview with the Oshawa Museum. “There was the Piano Works, McLaughlins, – no. The Piano Works, the Fittings, the Town Team, and Cedar Dale, and the Steel Range, and we had a town league you know. Well, that was interesting, really interesting.”

He talked about playing and how he enjoyed it.

“Right where Sam McLaughlin’s is,” he said. “That was the Prospect Park you know. That’s where we played, right at the back end of his place, that was beautiful.”

Pankhurst also spoke of the area having six hotels and named them all.

“There was the Queen’s, the Oshawa House, the Central, there was the American House, and the Brook House, and Mallet’s Hotel,” he said. “Every station, that’s the funny thing, but at every station on the Grand Trunk there always was a hotel.”

He had many memories of Cedar Dale, which became Oshawa in 1924, but according to Weymark, when it comes to history, what we think is the case is not the case historically.

“History is written by the victor in our area,” she said. “History is written by the wealthy white settler.”

“So those are the stories you see, right. As opposed to once we widen that lens. And outside of that, there’s so many more stories and experiences that you don’t see.”

Weymark said it’s important we take a “far more accurate,” inclusive look at the area’s history and that the Ontario Black Historical Society is a great place to start to get an idea of the lesser-known history of Oshawa

As for the Pankhurst brothers, Albert was the only one to have children and moved to the U.S. with his wife Martha Wiggins in 1923 and eventually settled in California, where they still have family today, according to Weymark.

Pankhurst lived in the family home with Greta until he died in 1978.